There are some basic principles of endurance training that we all should be following regardless of sport, according to Stephen Seiler. You haven’t heard of him? Perhaps that’s because he hasn’t written a best selling book or isn’t a coach (other than his daughter).

Stephen Seiler is one of the most widely cited researchers and sought after speakers on endurance sports. He has influenced research into training intensities for endurance athletes. His research tends to support polarized training, similar to Jack Daniels. Although, he is evidence based and continues to learn and adapts as he does more research and learns from elites.

Stephen Seiler is originally from Texas. He has been a professor of Sports Science at University of Agder, in Norway, for over two decades. He has done research and worked with teams and sports federations in a variety of endurance sports including cycling, triathlons, cross-country skiing, rowing, orienteering, speed skating, and running. He was a competitive rower, now mostly bikes.

In this article, I will summarize:

- Basic training principles for endurance athletes.

- Applications and concerns for older athletes.

- Interviews with elite athletes including Kilian Journet.

2 LTs and 3 Zones

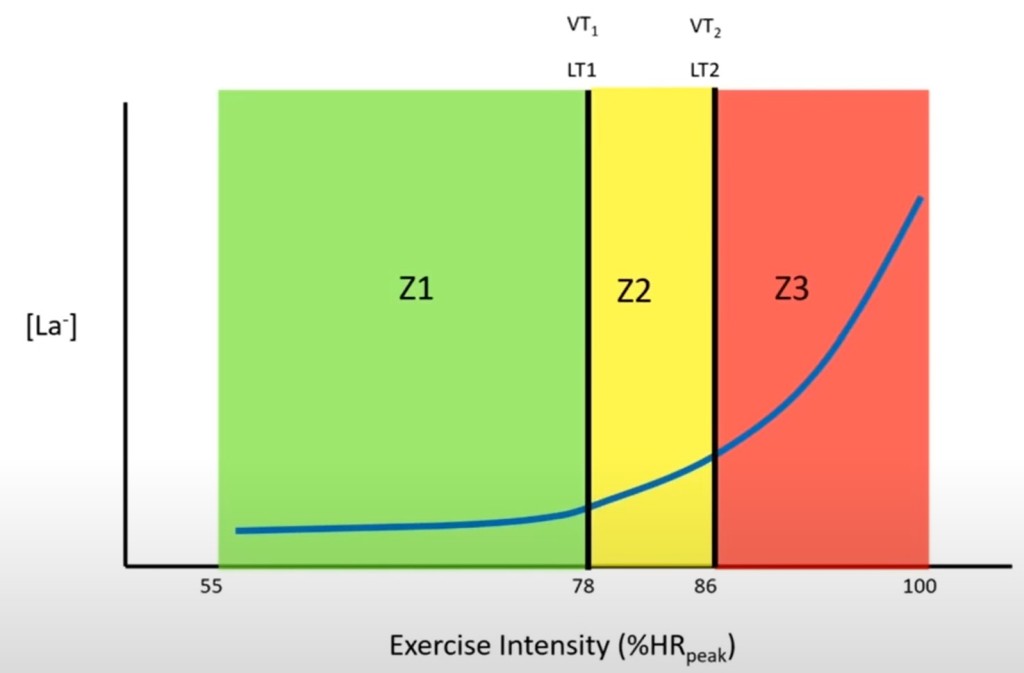

Lactate turn points are the key physiological factors that should drive training intensity. There are two of them. Briefly, lactate is a byproduct of metabolism, transport mechanism for energy, and fuel source. Lactate, produced via anaerobic/glycolic metabolism, can be transported to other muscles and organs, then converted into ATP, the fuel for muscles.

Lactate Turn Point 1 (LT1) is where there starts to be an increase of lactate in the blood system. Lactate is always present and is produced even at low effort levels. Below LT1, Zone 1 in the 3-zone model image (green), lactate is maintained and used locally. Above LT1, the local muscle is not able to utilize all the lactate being produced so it leaks out into the blood stream. LT1 is also called Ventilatory Threshold 1 (VT1) because that’s where the breathing first starts to become labored, where someone can hear your breathing – you have to breathe harder to expel more CO2, a byproduct of glycolic metabolism. LT1 and VT1 aren’t exactly the same, but they’re close enough. Monitoring your breathing is a great way to monitor your effort with or without a heart rate monitor. Other names for LT1/VT1 include: Onset of Blood Lactate Accumulation (OBLA), Aerobic Threshold (AeT), Maximum Aerobic Fitness (MAF from Phill Maffetone).

Zone 2 in the 3-zone model (yellow): As lactate leaks into the blood, it is transported to other parts of the body for energy including the brain, liver and heart. Blood lactate levels will continue to rise until they reach what’s calls a maximum lactate steady state (MLSS) up to LT2. Zone 2 is also known as Marathon Race Pace (MRP). In theory, you could continue to exercise at MRP as long as you can sufficiently fuel yourself with carbs. In reality, your muscles will fatigue.

LT2/Z3: Once your cross LT2, you are producing more lactate than your body can process. Blood lactate and cortisol levels shoot up quickly, breathing becomes harder (VT2), and recovery takes longer. Exhaustion hits in minutes rather than hours.

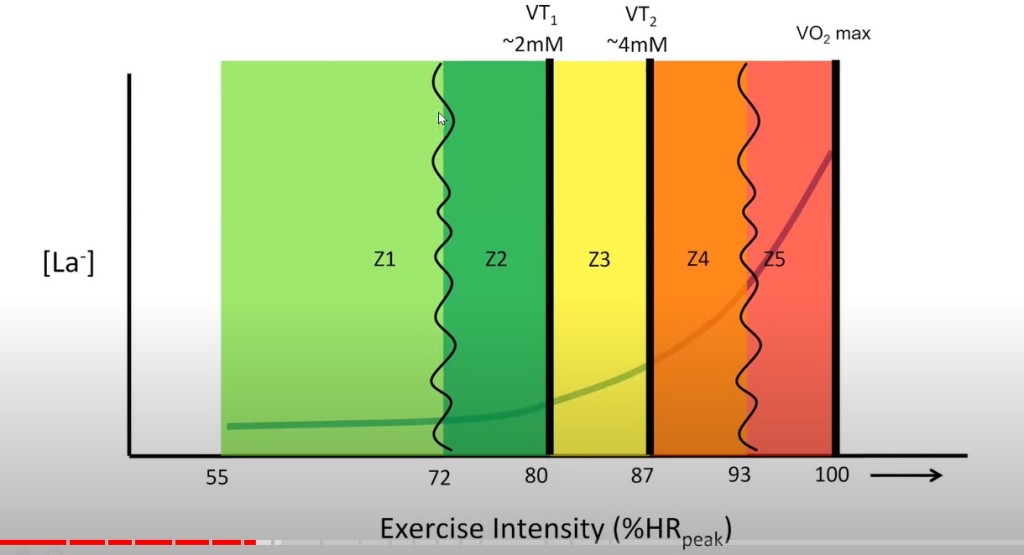

Seiler’s 3-zone model (left) is built around the physiological changes at the LTs. However, he accepts that some sports and coaches prefer a 5 (right) or more zone model. There isn’t a significant physiological difference between zones 1 & 2 or 4 & 5 in a 5-zone model. However, there can be value in designating a workout be Z1 so that the athlete doesn’t get anywhere close to LT1.

Most of your high intensity training (HIT) should be around LT2, high Z3 or low Z4 in a 5-zone model. You shouldn’t go into Z5 very often. Above LT2, lactate, cortisol, and other stress markers rise rapidly. Slightly lower intensity intervals allow for more volume and more training stimulus with less stress. Harder isn’t better. So, instead of doing your 400m, 1mi, 2km, etc. intervals almost as hard as you can, do them around LT2, typically somewhere between 10km and ½-marathon pace/effort. The Ingebrigtsen model has Jakob (and others) doing most of his intervals a bit below LT2. This allows him to do a higher volume of lactate training.

Some Z5 training is good when training for 10km, 5km, and shorter events. Such Z5 intervals should be in shorter intervals, with less volume, and be saved until you are getting closer to your goal race. E.g., 4-8 min hard, ~5k effort, with 1-2 min recovery.

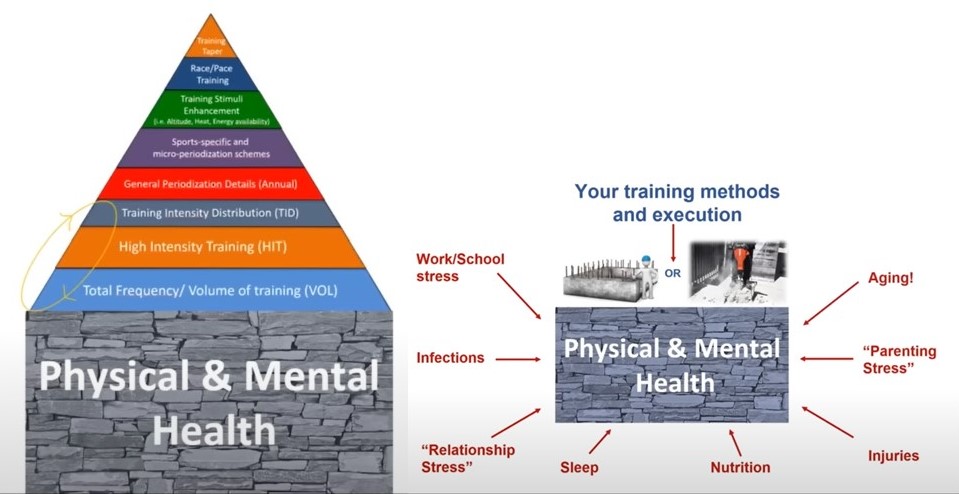

Buckets

Training stresses your body. Training damages muscles, tendons and bones, suppresses the immune system, impairs your sympathetic nervous system (seen via HRV), creates inflammation, and leads to mental fatigue. That stress is necessary to stimulate adaptation. However, stress should be managed. Too much stress (and not enough recovery) leads to your body breaking down rather than adapting and becoming stronger.

The vast majority of your training should be done at low intensities, below LT1, where stress is lower. There are a lot of beneficial adaptations that take place below LT1 without the added stress from going harder. You become more efficient in oxygen utilization. This pushes out the pace/effort of both LT1 & LT2.

Polarized, 80/20: Seiler believes that most of your training should be in the green bucket rather than yellow or red. However, 80/20 is more of a guardrail than a rigid rule. There are times when your green bucket training might be well > 80% (e.g., off and early season). Also, there may be time when your HIT might be well > 20%, in short blocks, for shorter goal races (e.g., 5km), close to your competition. Remember that racing counts as HIT. However, many athletes tend to do their low efforts too hard, which leads to not being able to reach or spend enough time at LT2. Planned green and red workouts end up being in the yellow bucket. The red arrows below indicate what many athletes tend to do, not what they should be doing.

Recovery tools – e.g., Normatec boots, ice baths, vitamin C, nsaids – that reduce inflammation, blunt the adaptive signal and, thus, the adaptive response. Such tricks might be OK if doing repeated races in a short period of time, like a stage race.

Other basic principles of endurance training across all endurance sports

- Build your aerobic base first before adding intensity.

- Aerobic base leads to higher VO2Max and LT even without HIT.

- Base building can be done in other sports. Runners, for example, can build their base with low impact and low intensity cycling, rowing and xc skiing.

- Running is different in that the stress from gravity – eccentric load on muscles, and impact on bones/joints – is much greater than almost every other endurance sport.

- Sport and race intensity specificity comes closer to your race/season.

- Consistency > details. Do the big things right. Worry less about the details.

- Success is not just what you do in the proximate season/training cycle. Adaptions over years of consistent training impact the current season.

- VO2Max peaks early in life, late teens – early 20s. Economy (speed at given oxygen uses) continues to increase as you age.

- Speed training for endurance athletes is different than Z4/5 training. It’s about training your fast twitch fibers to become stronger and fire more rapidly. Do this via short, 20-60 second sprints, with a lot of rest between. Don’t worry about HR or lactate.

- Stress is stress to your body. It doesn’t differentiate between exercise stress, a fight with your spouse, or being chased by a mountain lion. Life stresses impact your training and recovery. Training plans assume the best conditions. They should be modified around overall stress, health, weather, etc.

Masters athletes

As we get older, performance ability declines. This is due to three main factors:

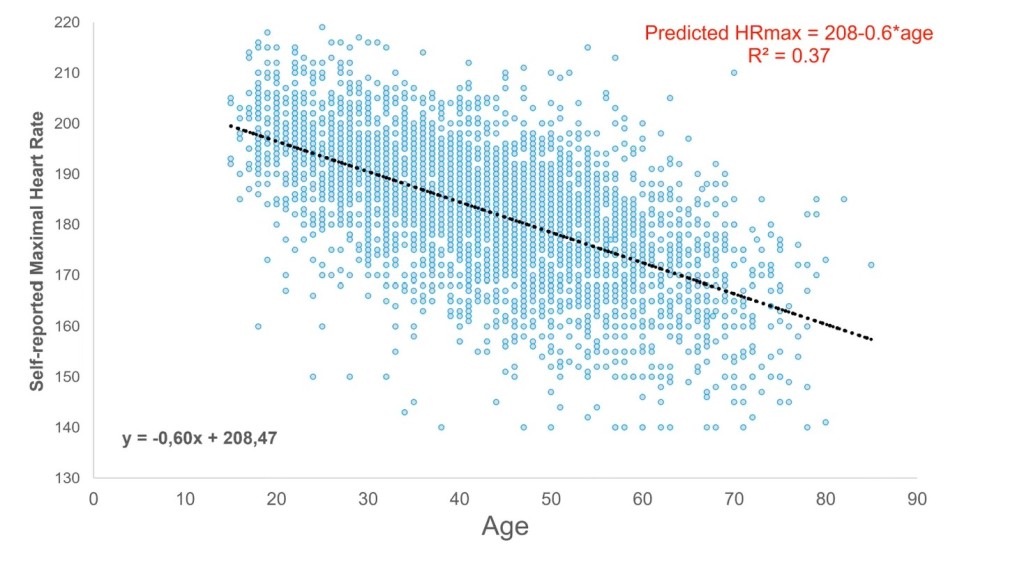

- Max HR declines.; 208-.68a. Formulas (e.g., 220-age; or men: 209.6 – .72age, women: 207.2 – .65age) summarize for populations, but there is a lot of individual variation. If you are using max HR, you should get yours tested, or at least have a good idea through experience, rather than relying on formulas. Because max HR declines, LT1 as % of max goes up.

- Lose muscle mass (sarcopenia). We lose type 2, fast twitch fibers faster, the ones for speed and explosive power. This is why older athletes tend to move to longer, slower events. This decline accelerates as we get older. We lose quantity, not the quality of muscles; force per fiber stays. We also tend to add more sub-cutaneous fat.

- Lose tendon elasticity. He calls achilles ruptures an old man disease.

To counter the loss of muscle mass, older athletes should include strength training. Strength training should not be just sport specific. Strength training is beneficial for overall health. Thus, strength training should include muscles not central to your sport; runners should train their arms and shoulders, not just their legs.

Interviews and Videos

Seiler has a number of good videos on his YouTube channel. This includes long interviews with some elite athletes. Here are summaries of a couple of them.

Kilian Journet: Kilian spends months doing Z1/2. Able to race well at short, high intensity, Skimo races, for example, without HIT, because of his aerobic base and history of HIT over years. He does most of his technical running on easy days. He was raised at altitude but now lives at sea level. He adapts to altitude easily perhaps, because, he has gone up and down so much, his body knows how to adapt. He came to Colorado only a couple of days before last year’s Hardrock, where he set the record. Surprisingly, his hemoglobin levels aren’t that high. He thinks he does well at altitude because of large capillarization and lung capacity rather than blood chemistry.

Nils Van Der Poel: Nils set world records and won gold medalist in both the 5000m and 10000m, at the 2022 Winter Olympic. He spent a lot of time running ultras and racing road bikes before returning to speed skating Even when he did return, he still did most of his training on the bike since ice oval availability is limited, and the body can only so much time in a speed skating position. Cycling simulates skating well. Two of America’s greatest speed skaters were also great cyclists – Connie Carpenter-Phinney (1972 winter Olympics at 14yo, first women’s cycling gold medal at the 1984 Olympics) and Eric Heiden (5 gold medals at the 1980 winter games, then pro tour rider). Nils followed a 5/2 training plan during his Olympic prep. He trained hard Mon – Fri, then took the weekends off. This is not for everyone, but interesting to think about.

Stephen Seiler’s YT channel. He has many videos. Here are a few:

- Shared (across sports) Model of Endurance Training – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fy-zMq6-DYY&t=1822s

- Trainable Components of Endurance – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otNngp1u-Ls

- Sustainable Training for Masters Athletes – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kC5_0qOJhDk&t=1711s

- Load, Stress, Strain – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BwL9ehjgCsQ

- Speed development sessions for distance runners – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JS2x34tPXW0

- TED talk – How “normal people” can train like the worlds best endurance athletes. https://www.ted.com/talks/stephen_seiler_how_normal_people_can_train_like_the_worlds_best_edurance_athletes

Train smart! Have fun! Smile frequently!

See you on the roads and trails.

www.runuphillracing.com

When in doubt, run uphill!